Two Kingdoms, Two Writers

Exodus 32 is a story that shows that after Israel escapes Egypt that their first apostate is none other than Aaron, the High Priest. In this account Aaron gives in to the wishes of the people by fashioning a golden calf while Moses is up on Mount Sinai talking with the Lord. When Moses comes down from the mountain, he sees the horrible apostasy of the Israelites and punishes them by having the Levites kill 3,000 of what seem to be the most rebellious of the lot.

Exodus 32 is a story that shows that after Israel escapes Egypt that their first apostate is none other than Aaron, the High Priest. In this account Aaron gives in to the wishes of the people by fashioning a golden calf while Moses is up on Mount Sinai talking with the Lord. When Moses comes down from the mountain, he sees the horrible apostasy of the Israelites and punishes them by having the Levites kill 3,000 of what seem to be the most rebellious of the lot.

There are many clues in the text to suggest that this narrative is the production of scribes from the northern tribes of Israel who wish to denigrate not only Aaron, but the House of Aaron, or the Aaronid Priests in Judah, as well as the leader of the northern tribes, Jeroboam, who reigned around 922-901 B.C.E. I also find evidence in the text to suggest that this narrative has been through a couple of redactions, or editions, with the first edition of the text portraying Aaron in a positive fashion, only later to then have scribes do some creative work with the text to make Aaron to appear in a negative light, thus creating the first apostate in Israel in Moses’ era.

The Golden Calf

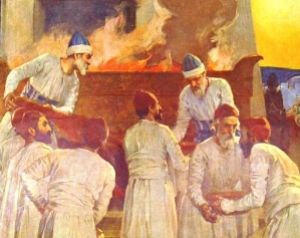

The most revealing of all is the E story of the golden calf, which tells us that while Moses is busy getting the commands from the Lord, Aaron makes a golden calf for the Israelites. The Lord tells Moses that the people are busy worshiping this calf when he tells Moses that the people said, “These by thy gods, O Israel, which have brought thee up out of the land of Egypt” (Exodus 32:8). Aaron tells the people “Tomorrow is a feast to the Lord” (Exodus 32:5). All the children of Israel feast and worship the calf.

The most revealing of all is the E story of the golden calf, which tells us that while Moses is busy getting the commands from the Lord, Aaron makes a golden calf for the Israelites. The Lord tells Moses that the people are busy worshiping this calf when he tells Moses that the people said, “These by thy gods, O Israel, which have brought thee up out of the land of Egypt” (Exodus 32:8). Aaron tells the people “Tomorrow is a feast to the Lord” (Exodus 32:5). All the children of Israel feast and worship the calf.

While all of this is going on, God tells Moses that he will destroy the people and start over with new children, a new family descended from Moses (Exodus 32:10). Moses tells the Lord that if he does destroy the Israelites, essentially the Egyptians will make fun of God for liberating his people, only to destroy them later. What will the world say about Jehovah? In this text, God changes his mind, the KJV says that “the Lord repented of the evil which he thought to do unto his people” (Exodus 32:14).

Moses comes down off the mountain with his assistant Joshua. When he sees the calf and the condition of the Israelites, he breaks the stone tablets (Exodus 32:19). Moses asks Aaron about the calf and his response is quite funny. Aaron says, “Moses, you know these people, they are always up to mischief! They said to me, Make us gods, which shall go before us… And I said unto them, Whosoever hath any gold, let them break it off. So they gave it me: then I cast it into the fire, and there came out this calf” (Exodus 32:22-24).

Moses then asks the people who is on the Lord’s side, after which Moses has the Levites slay 3,000 of those who apparently decided not to be on the Lord’s side (Exodus 32:28).

I appreciate the commentary by Richard Friedman when he asks the following questions of this story:

The story is all questions. Why did the person who wrote this story depict his people as rebellious at the very time of their liberation and their receiving the covenant? Why did he picture Aaron as leader of the heresy? Why does Aaron not suffer any punishment for it in the end? Why did the author picture a golden calf? Why do the people say “These are your gods, Israel…,” when there’s only one calf there? And why do they say “… that brought you up from the land of Egypt” when the calf obviously was not made until after they were out of Egypt? Why does Aaron say “A holiday to Yahweh tomorrow” when he is presenting the calf as a rival to Yahweh? Why is the calf treated as a god in this story, when the calf was not a god in the ancient Near East? Why did the writer picture Moses as smashing the tablets of the Ten Commandments? Why picture the Levites as acting in bloody zeal? Why include Joshua in the story? Why depict Joshua as dissociated from the golden calf event? 1

If we choose to understand the Bible as a text that comes to us from different authors with different perspectives, we can piece together what is happening in this story of the golden calf. But it is essential that we begin with a couple of assumptions.

If we begin with the assumption that the J stories in the Bible come to us from the south, or from Judah, and that the E stories come to us from the north, from the kingdom of Israel, we can begin to see what is going on in this narrative. We can begin to see that the author of this northern text is superimposing Aaron over Jeroboam, showing us how Aaron is type for Jeroboam, the apostate king who the scribes of the north wish to denigrate as they work to produce this text. This assumption will help us to unlock what is actually going on in Exodus 32.

Again from Richard Friedman, we read the following:

We already have enough information from our acquaintances with the world that produced the Bible to answer all of these questions. We have already seen considerable evidence that the author of J was from Judah and the author of E from Israel. We have also seen evidence that suggests that the Israelite author of E had a particular interest in matters that related to King Jeroboam and his policies. E deals with cities that Jeroboam rebuilt: Shechem, Penuel, Beth-El. E justifies the ascendancy of his home tribe, Ephraim. E disdains the Judean policy of missim. E gives special attention to the matter of the burial of Joseph, whose traditional gravesite was in Jeroboam’s capital, Shechem. Further, E is a source which particularly emphasizes Moses as its hero, much more than J does. In this story, it is Moses’ intercession with God that saves the people from destruction. E also especially develops Moses’ personal role in the liberation from slavery, in a way that J does not. In E there is less material on the patriarchs than on Moses; in J there is more on the patriarchs.

Let us consider the possibility that the person who wrote E was a Levitical priest, probably from Shiloh, and therefore possibly descended from Moses. Such a person would have an interest in developing these things: the oppressive Judean economic policies, the establishment of an independent kingdom under Jeroboam, and the superior status of Moses. If this is true, that the author of E was a Shiloh Levite possibly descended from Moses, then this answers every one of the questions about the golden calf story.

Recall that the priests of Shiloh suffered the loss of their place in the priestly hierarchy under King Solomon. Their chief, Abiathar, was expelled from Jerusalem. The other chief priest, Zadok, who was regarded as a descendant of Aaron, meanwhile remained in power. Northern Levites’ lands were given to the Phoenicians. The Shiloh prophet Ahijah instigated the northern tribes’ secession, and he designated Jeroboam as the northern king. The Shiloh priests’ hopes for the new kingdom, however, were frustrated when Jeroboam established the golden calf religious centers at Dan and Beth-El, and he did not appoint them as priests there. For this old family of priests, what should have been a time of liberation had been turned into a time of religious betrayal. The symbol of their exclusion in Israel was the golden calves. The symbol of their exclusion in Judah was Aaron. Someone from that family, the author of E, wrote a story that said that soon after the Israelite’s liberation from slavery, they committed heresy. What was the heresy? They worshiped a golden calf! Who made the golden calf! Aaron!

Recall that the priests of Shiloh suffered the loss of their place in the priestly hierarchy under King Solomon. Their chief, Abiathar, was expelled from Jerusalem. The other chief priest, Zadok, who was regarded as a descendant of Aaron, meanwhile remained in power. Northern Levites’ lands were given to the Phoenicians. The Shiloh prophet Ahijah instigated the northern tribes’ secession, and he designated Jeroboam as the northern king. The Shiloh priests’ hopes for the new kingdom, however, were frustrated when Jeroboam established the golden calf religious centers at Dan and Beth-El, and he did not appoint them as priests there. For this old family of priests, what should have been a time of liberation had been turned into a time of religious betrayal. The symbol of their exclusion in Israel was the golden calves. The symbol of their exclusion in Judah was Aaron. Someone from that family, the author of E, wrote a story that said that soon after the Israelite’s liberation from slavery, they committed heresy. What was the heresy? They worshiped a golden calf! Who made the golden calf! Aaron!

The details of the story fall into place. Why does Aaron not suffer any punishment in the story? Because no matter how much antipathy the author may have felt toward Aaron’s descendants, that author could not change the entire historical recollection of his people. They had a tradition that Aaron was an ancient high priest. The high priest cannot be pictured as suffering any hurt from God because in such a case he could not have continued to serve as high priest. Any sort of blemish on the high priest would have disqualified him from service. The author could not just make up a story that the high priest had become disqualified at this early stage.

Why does Aaron say “A holiday to Yahweh tomorrow” when he is presenting the calf as a rival to Yahweh? Because the calf is not in fact a rival god. The calf, or young bull, is only the throne platform or symbol of the deity, not a deity itself. Why is the calf treated as a god in this story? Presumably because the story is polemical; the writer means to cast the golden calves of the kingdom of Israel in the worst light possible. In fact, we shall see other cases in which biblical writers use the word “gods” to include the golden calves and the golden cherubs; and in those cases, too, the text is polemical.

Why do the people say “These are your gods, Israel …” when there is only one calf? Why do they say “… that brought you up from the land of Egypt” when the calf was not made until they were out of Egypt? The answer seems to lie in the account of King Jeroboam in the book of 1 Kings. It states there that when Jeroboam made his two golden calves he declared to his people, “Here are your gods, Israel, that brought you up from the land of Egypt.” The people’s words in Exodus are identical to Jeroboam’s words in 1 Kings. It would be difficult for us to trace the textual history of these two passages now, but at minimum we can say that the writer of the golden calf account in Exodus seems to have taken the words that were traditionally ascribed to Jeroboam and placed them in the mouths of the people. This made the connection between his golden calf story and the golden calves of the kingdom of Israel crystal clear to his readers.

Why did the writer of E picture the Levites as acting in bloody zeal? He was a Levite. He wrote that Aaron had acted rebelliously while the other Levites alone acted loyally. Moses tells the Levites there that they have earned blessing by their actions. The story thus denigrates the ancestry of the Jerusalem priests while praising the rest of the Levites.

What is Joshua doing in this story, and why is he singled out as being dissociated from the heresy? Because, as we know, Joshua was a northern hero. His home tribe was the same as King Jeroboam’s: Ephraim. His gravesite, like Joseph’s, was in Ephraim. He is credited with having led a national covenant ceremony at Shechem, the place that was later to become Jeroboam’s capital. The E writer therefore was adding to the golden calf story an element of praise for a northern hero who was associated in the tradition with the capital city and the preeminent tribe. The dissociation of Joshua from the golden calf heresy also explained why Joshua later becomes Moses’ successor.

Why did the writer picture Moses as smashing the tablets of the Ten Commandments? Possibly because this raised doubts about Judah’s central religious shrine. The Temple in Judah housed the ark that was supposed to contain the two tablets of the Ten Commandments. According to the E story of the golden calf, Moses smashes the tablets. That means that according to the E source the ark down south in the Temple in Jerusalem either contains unauthentic tablets or no tablets at all.

Why did the writer picture Moses as smashing the tablets of the Ten Commandments? Possibly because this raised doubts about Judah’s central religious shrine. The Temple in Judah housed the ark that was supposed to contain the two tablets of the Ten Commandments. According to the E story of the golden calf, Moses smashes the tablets. That means that according to the E source the ark down south in the Temple in Jerusalem either contains unauthentic tablets or no tablets at all.

The author of E, in fashioning the golden calf story, attacked both the Israelite and the Judean religious establishments. Both had excluded his group. One might ask, why, then, was this writer so favorable to Jeroboam’s kingdom in other stories? Why did he favor the cities of Shechem, Penuel, and especially Beth-El? Why did he favor the tribe of Ephraim? First, because Shiloh was in Ephraim, and its great priest Samuel was from Ephraim. Second, presumably because the kingdom of Israel remained his only hope politically. He could look forward to a day when the illegitimate, non-Levite priests of Beth-El would be rejected, and his Levite group would be reinstated. Judah and Jerusalem offered no such hope at that time. The priests of the family of Aaron had been firmly established there since King Solomon’s time. They were Levites and therefore no less legitimate than the priests of Shiloh. They were closely tied by bonds of politics and marriage to the royal family. The only realistic hope for the Shiloh priests was in the northern kingdom. The E source therefore favored that kingdom’s political structure while attacking its religious establishment.

Symbols of Faith

The golden calf story is not the only instance in which the author of E may have been criticizing both the northern and southern religious establishments.

In the J version of the commandments that God gives to Moses on Mount Sinai, there is a prohibition against making statues (idols). The wording of the J commandment is:

You shall not make for yourself molten gods. (Exodus 34:17)

The J command here forbids only molten statues. The golden calves of Jeroboam in the north were molten. The golden cherubs of Solomon in the south were not molten. They were made of olive wood and then gold-plated. The J text thus fits the iconography of Judah. It may imply that the golden calves of northern Israel are inappropriate, even though they are not actually statues of a god; but it does not leave itself open to the countercharge that Judah’s golden cherubs are inappropriate as well.

Meanwhile, the E source’s formulation of this prohibition reads:

You shall not make with me gods of silver and gods of gold.

You shall not make them for yourselves. (Exodus 20:23)

Perhaps this command refers only to actual statues of gods, but if it casts doubt on the throne-platform icons as well then it casts doubt on both the molten golden calves and the plated golden cherubs.

The relationship between the J and E sources and the religious symbols of Judah and Israel respectively is evident elsewhere as well. In a J text at the beginning of the book of Numbers the people set out from Sinai/Horeb on their journey to the promised land. According to the description of their departure, the ark is carried in front of the people as they travel. Another J text also mentions the ark as important to the people’s success in the wilderness. It in fact suggests that it is impossible to be militarily successful without it. (Numbers 14:44) The ark, as we know, was regarded as the central object of the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that it is treated with such importance in J, but it is never mentioned in E.

E rather attributes much importance to the Tent of Meeting as the symbol of the presence of God among the people. (Exodus 33:7-11) The Tent of Meeting (or Tabernacle), according to the books of Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles, was a primary site of the nation’s worship until Solomon replaced the tent shrine with the Temple. The Tabernacle, moreover, was associated originally with the city Shiloh. Given the other evidence for connecting the author of E with the priesthood of Shiloh, it should come as no surprise, therefore, that the Tent of Meeting has such importance in E, but it is never mentioned in J.

E rather attributes much importance to the Tent of Meeting as the symbol of the presence of God among the people. (Exodus 33:7-11) The Tent of Meeting (or Tabernacle), according to the books of Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles, was a primary site of the nation’s worship until Solomon replaced the tent shrine with the Temple. The Tabernacle, moreover, was associated originally with the city Shiloh. Given the other evidence for connecting the author of E with the priesthood of Shiloh, it should come as no surprise, therefore, that the Tent of Meeting has such importance in E, but it is never mentioned in J.

The ark does not appear in E. The Tabernacle does not appear in J. This is no coincidence. The stories in the sources treat the religious symbols of the respective communities from which they came. Now we can also turn back to the beginning of the book of Genesis and appreciate the fact that at the conclusion of the story of Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden, which is a J narrative, Yahweh sets cherubs as the guardians of the path to the tree of life. (Genesis 3:24) Since cherubs were in the Holy of Holies in the Jerusalem Temple, it is only natural that an advocate of Judah’s religious traditions should picture cherubs as the guardians of something valuable and sacred.

The ark does not appear in E. The Tabernacle does not appear in J. This is no coincidence. The stories in the sources treat the religious symbols of the respective communities from which they came. Now we can also turn back to the beginning of the book of Genesis and appreciate the fact that at the conclusion of the story of Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden, which is a J narrative, Yahweh sets cherubs as the guardians of the path to the tree of life. (Genesis 3:24) Since cherubs were in the Holy of Holies in the Jerusalem Temple, it is only natural that an advocate of Judah’s religious traditions should picture cherubs as the guardians of something valuable and sacred.

The golden calf story reveals more about its author than probably any other story in J or E. In addition to all that it tells us about its author’s background and about its author’s skill in fashioning a story, it conveys how deep his anger was toward those who had displaced his group in Judah and in Israel. He could picture Aaron, ancestor of the Jerusalem priesthood, as committing heresy and dishonesty. He could picture the national symbols of Israelite religion as objects of idolatry. He could picture the nation who accepted these symbols as deserving a bloody purge. What he pictured Moses doing to the golden calf was what he himself might have liked to do to the calves of Dan and Beth-El: burn them with fire, grind them thin as dust. 2

The First Edition of the Golden Calf Narrative

There is evidence to suggest that Aaron is presented in a positive light in the first edition of this story. Moses is not on the scene, as he is on the mountain speaking with Jehovah. Aaron is with the people, who wish to commune with god. Aaron is portrayed here rather positively, especially if we can see this story in the context of the Ancient Near East.

In this account we read a part of the narrative that I always viewed as a bit of Biblical humor. We read Aaron telling Moses, “I said unto them, Whosoever hath any gold, let them break it off. So they gave it me: then I cast it into the fire, and there came out this calf” (Exodus 32:24).

In this text, Aaron essentially denies responsibility for making the calf, for it made itself! There is evidence to suggest here that there was a version of this story where Aaron is viewed favorably. There is midrashic commentary that tells us that the Mishkan, or the Tabernacle was miraculously constructed, much in the way that the golden calf was constructed. In this account we read:

Because when they had finished the Mishkan, none knew how to set it up. So what did they do? Each one took his finished piece of work and … as soon as Moses beheld them, the Divine spirit settled upon him and he set the Tabernacle up.

You must not say that it was Moses who set it up, for miracles were performed with it and it rose of its own accord, for it says, “The Mishkan was erected” (Ex. 40:17). [Just like when Solomon built the Temple,] everyone was helping him, including both man and spirits, because it says: “For the house, in its being built…” (I Kings VI, 7) – [that is,] it was built of its own accord. Therefore it must have been built miraculously. Similarly, when the Mishkan was erected, it also rose up miraculously. 3

There is more evidence to this spontaneous and miraculous creation, found in the Ugaritic narratives surrounding Baal and his house. In the Ugaritic myth we read of stories of how Baal is sent to the earth to battle the forces of chaos, and once he is victorious, a house is created for him on Mount Zapon. In this story we read how the House of Baal built itself miraculously by simply firing silver and gold for six days. In this account we read:

Mighty Balu speaks up:

Hurry! (raise) a house, O Kotaru,

Hurry! Raise a palace,

Hurry! You must build a house.

Hurry! You must raise a palace

On the heights of Sapanu

A house covering a thousand acres,

A palace (covering) ten thousand hectares…

Fire is placed in the house,

Flames in the palace.

For a day, two (days),

The fire consumes (fuel) in the house,

The flames (consume fuel) in the palace;

For a third, a fourth day,

The fire consumes (fuel) in the house,

The flames (consume fuel) in the palace;

For a fifth, a sixth day,

The fire (consumes fuel) in the palace;

Then on the seventh day,

The fire is removed from the house,

The flames from the palace.

(Voila!) the silver has turned into plaques,

The gold is turned into bricks.

(This) brings joy to Mighty Balu:

You have built my house of silver,

My palace of gold.

(Then) Balu completes the furnishing of (his) house,

Haddu completes the furnishing of his palace. 4

Clearly there is evidence to suggest that Aaron was acting in a role where the God who had protected the Israelites was demonstrating his approval of Aaron’s work in the miraculous way that the calf was created. Both from Midrashic and Canaanite texts, the precedence is set for this possibility. After the northern priests were banished from their roles in the northern country of Israel (1 Kings 12:28-31), then coming down into the area of Jerusalem with their texts, the evidence suggests the possibility that these priests and scribes repackaged the story of Aaron and the golden calf, casting Aaron in a negative light as an apostate, also denigrating King Jeroboam, with a stroke of their pen in these texts that they were creating. Understanding this historical situation, as well as seeing the northern influence of the Elohist author helps us to see Exodus 32 in a different light. It answers all of the questions addressed by Friedman, and helps us to see the blending of human and divine influences both in the texts and the history of the people who created them.

Notes

- Richard Friedman, Who Wrote the Bible? Harper One, 1997, p. 71.

- Ibid., p. 70-76.

- Shemot Rabbah 52:4. See: Who Built the Mishkan? By Rabbi Dov Linzer, March 8, 2011, emphasis added.

- Pardee in W.W. Hallo and K. L. Younger, eds., The Context of Scripture, volume 1, p. 260-261.

No Comments

Comments are closed.