The Construction of the Synoptic Gospels

The Authors of the Synoptics used many sources

Based on the evidence that scholars have produced in our day, it is evident that the authors of the gospels in the New Testament quoted from other sources. I once had a discussion about this idea when I mentioned in passing that Mathew and Luke quote heavily from Mark. I may have caused some consternation when the individual said, “Are you saying that Matthew didn’t write Matthew?”

Based on the evidence that scholars have produced in our day, it is evident that the authors of the gospels in the New Testament quoted from other sources. I once had a discussion about this idea when I mentioned in passing that Mathew and Luke quote heavily from Mark. I may have caused some consternation when the individual said, “Are you saying that Matthew didn’t write Matthew?”

My point in mentioning that Matthew was using Mark to put his text together (whoever wrote Matthew isn’t something I think we really know, nor can we know at this point) in no way takes anything away from the fact that the text of Matthew was written or composed by the author. It does not take away from the inspiration of the text either in my opinon. This is how the texts of the scriptures, in many instances, came to be. Prophets and authors of scriptural texts are quoting each other all the time. This is a common method of scriptural production.

In the Book of Mormon, Alma quoted liberally from other inspired authors. In his address to the poor Zoramites, Alma alludes to Zenos, Zenock, and Moses, leading the reader to believe that even these individuals with lower socioeconomic status were familiar with teachings from the brass plates (see Alma 33:3–20). Helaman’s counsel to his sons Nephi and Lehi indicates that they had access to the works of previous prophets as well.

He told them, “O remember, remember, my sons, the words which king Benjamin spake unto his people. . . . And remember also the words which Amulek spake unto Zeezrom, in the city of Ammonihah” (Hel. 5:9–10). “Nephi and Lehi likely used the precise words of King Benjamin in their preaching, just as their father had quoted to them some of the words of King Benjamin: ‘Remember that there is no other way nor means whereby man can be saved, only through the atoning blood of Jesus Christ’ (Helaman 5:9, compare Mosiah 3:18; 4:8).” 1

We have multiple examples in the small plates where Nephi quotes heavily from the prophet Isaiah as well. Nephi tells us that he is doing this when he quotes Isaiah. He also uses other ancient sources on the Brass Plates in the construction of scripture when he testifies of Jesus Christ as the Savior who will come to redeem mankind. In 1 Nephi 19:10 we read:

And the God of our fathers, who were led out of Egypt, out of bondage, and also were preserved in the wilderness by him, yea, the God of Abraham, and of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, yieldeth himself, according to the words of the angel, as a man, into the hands of wicked men, to be lifted up, according to the words of Zenock, and to be crucified, according to the words of Neum, and to be buried in a sepulchre, according to the words of Zenos, which he spake concerning the three days of darkness, which should be a sign given of his death unto those who should inhabit the isles of the sea, more especially given unto those who are of the house of Israel.

This is a classic example where the author tells us who he is quoting, and for what purpose. But there are many examples of prophets quoting other previous prophets, creating nuanced intertextual relationships, oftentimes even creating new meanings of texts in the process.

John Hilton had this to say about Nephite prophets quoting earlier prophets in their works:

The fact that later Nephite prophets had access to the words of earlier ones opens the possibility for intentional intertextual quotations and allusions within the Book of Mormon. Dubious readers may see repetitive words or phrases in the Book of Mormon as evidence of a stuttering problem. When looked at through an intertextual lens, however, the repetition may be most illuminating. Exploring intertextuality within the Book of Mormon is a fruitful area of study. 2

As Kerry Muhlestein has pointed out, “Intertextual studies have become important in biblical scholarship as well as in the study of other sacred texts. In recent decades, biblical studies have been greatly enhanced by an understanding of how certain scriptural themes and ideas developed throughout Israelite history as evidenced by intertextual studies. Rarely has this type of work been applied to the Book of Mormon.” 3

John Welch has found multiple examples of later prophets quoting earlier ones in the Book of Mormon. For example, Alma quotes twenty-one words from Lehi and Samuel the Lamanite quotes King Benjamin. (see and compare Alma 36:22 to 1 Nephi 1:8 and Helaman 14:12 to Mosiah 3:8)

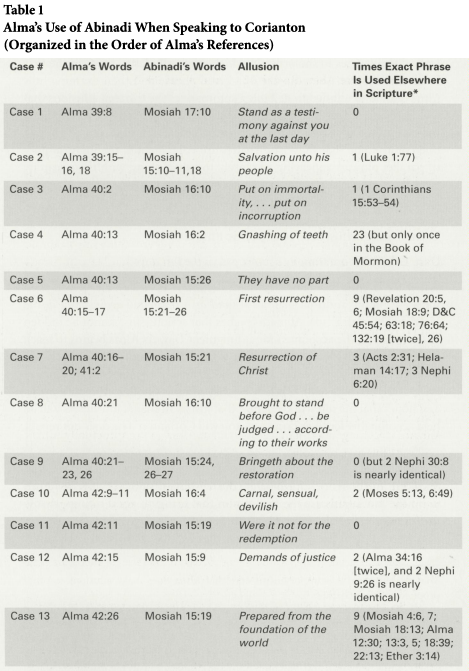

Alma uses the words of Abinadi to teach the people as well. This type of teaching and scriptural production was commonly used among Book of Mormon prophets (see table below).

What we think we know about the Synoptic Gospels

Many scholars of the New Testament believe that Matthew and Luke used the Gospel of Mark as source material for their accounts of the life of Jesus Christ. This assertion, of course, leads us to other questions that must be addressed in our quest to more fully understand the gospels.

Matthew, Mark, and Luke are often called “The Synoptic Gospels.” This is because they “see the same,” or tell the same stories about the life of Jesus. Not only do these accounts tell many of the same stories, they often do so using the exact same words. This fact is virtually impossible unless these stories are derived form a shared literary source.

What makes the synoptic gospels so interesting to study, besides the subject matter (the life of Jesus), is the fact that although these accounts often agree, they also disagree in many places. The problem of how to explain the varied agreements and disagreements among these texts is called “The Synoptic Problem.”

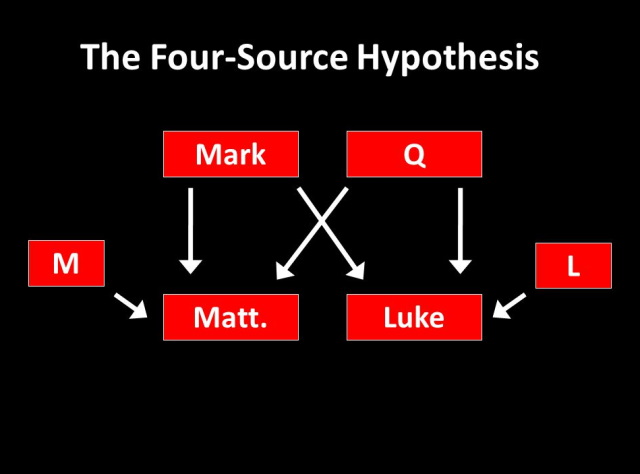

Scholars have propounded a number of theories over the years to solve the Synoptic Problem. Many of the theories are extraordinarily complex and entirely unlikely. The least problematic of the solutions of the Synoptic Problem is sometimes called the “four-source hypothesis.” According to this hypothesis, Mark was the first Gospel to be written. It was used by both Matthew and Luke. In addition, both of these other Gospels had access to another source, called Q (from the German word for “source,” Quelle). Q provided Matthew and Luke with the stories that they have in common that are not, however, found in Mark. Moreover, Matthew had a source (or group of sources) of his own, from which he drew stories found in neither of the other Gospels. Scholars have simply labeled this source (or sources) M (for Matthew’s special source). Likewise, Luke had a source (or group of sources) for stories that he alone tells; not surprisingly, this is called L (Luke’s special source). Hence, according to this hypothesis, four sources lie behind the three Synoptic Gospels: Mark, Q, M, and L.

The cornerstone of the four source hypothesis is the theory that Matthew and Luke both used Mark. This is what scholars have generally called “Markan priority.”

Arguments for Markan Priority

Since the main reason for thinking that the Gospels share a common source is their verbatim agreements, it makes sense to examine the nature of these agreements in order to decide which of the books was used by the other two. If you were to make a detailed comparison of the word for word agreements among these Gospels, an interesting pattern would emerge. Sometimes all three of the Gospels tell a story in the exact same fashion. This can easily be accounted for; it would happen whenever two of the authors borrowed their account from the earliest one, and neither of them changed it. Sometimes all three of the Synoptic Gospels vary in the wording or emphasis of a story. This would happen whenever the two authors who borrowed the story each changed it, but did so in different ways. Finally, sometimes two of the three are exactly alike, but the third account disagrees in some way. This would occur when both of the later authors borrowed the story but only one of them altered it; in this case one of the editors or redactors would agree with the wording of his source, and the other would not.

In this kind of situation, certain patterns of agreement naturally occur among the Synoptics Gospels. Sometimes Matthew and Mark share the wording of a story when Luke varies somewhat, and sometimes Mark and Luke share the wording when Matthew differs. But it is terrifically unusual to find Matthew and Luke sharing the wording of a story also found in Mark when Mark doesn’t agree. The reason for this, according to modern Biblical scholarship, is due to the fact that Mark was a primary source that Matthew and Luke used to construct their texts. This, in essence, is what we mean by “Markan Priority.” This is how these texts were constructed, at least in part.

As Bart Ehrman stated:

If Matthew were the source for Mark and Luke, or if Luke were the source for Matthew and Mark, you would probably not get this pattern. Consider these examples. If both Matthew and Luke used Mark, then sometimes they would both reproduce the same wording. That’s why all three sometimes agree. Sometimes they would both change the wording for reasons of their own. That’s why all three sometimes differ. Sometimes Matthew would change Mark’s account when Luke left it the same. That’s why Mark and Luke sometimes agree against Matthew. And sometimes Luke would change Mark’s account when Matthew left it the same. That’s why Matthew and Mark sometimes agree against Luke.

The reason then that Matthew and Luke rarely agree against Mark in the wording of stories found in all three is that Mark is the source for these stories. Unless Matthew and Luke accidentally happen to make precisely the same changes in their source (which does happen on occasion, but not commonly and not in major ways), they cannot both differ from the source and agree with one another. The fact that they rarely do differ from Mark while agreeing with one another indicates that Mark must have been their source. 4

There are many other arguments for Markan Priority. Matthew and Luke seem to correct grammatical errors in Mark, as well as taking more difficult readings of Mark’s text and simplifying it, something that would evidence the priority of Mark. The theology of Mark seems to be something that fits into an earlier time period as well, something that I hope to write about later.

The Q Source

Once we have established that Mark is the source of much of Matthew and Luke, the Q hypothesis arises as the next source that was used in the construction of these two texts. Matthew and Luke each have stories in common that are not found anywhere in Mark, and in some instances these stories agree in exactness. Where did Luke and Matthew obtain these accounts of the life of Jesus?

It is unlikely that one of the authors used Mark, added several stories of his own, and that his account then served as the source for the other. If this were the case, we would not be able to explain the phenomenon that these accounts of the life of Jesus found in Matthew and Luke but not in Mark are almost always inserted by these authors into a different sequence of Mark’s narrative. Why would an author follow the sequence of one of his sources, except for stories that are not found in his other one? It is more likely that these stories were drawn from another source that no longer exists, the source that scholars have designated as Q.

We do not know the full extent or the entire character of Q. It is best to identify Q as material that both Matthew and Luke have in common that we do not have anywhere in the Gospel of Mark. It is good to note that Q is comprised of the sayings of Jesus. Many scholars think that Q must have been a written document, for the simple reason that there are long stretches of material in both Matthew and Luke that are in verbatim agreement, thereby making the argument for Q as a written document as opposed to an oral tradition. (On the matter of whether Q was written, Tuckett writes (The Anchor Bible Dictionary, v. 5, p. 568): “The theory that Q represents a mass of oral traditions does not account for the common order in Q material, which can be discerned once Matthew’s habit of collecting related material into his large teaching discourses is discounted (Taylor 1953, 1959). Such a common order demands a theory that Q at some stage existed in written form.”

On the provenance of Q, Udo Schnelle stated:

The Sayings Source presumably originated in (north) Palestine, since its theological perspective is directed primarily to Israel. The proclamations of judgment at the beginning and end of the document are directed against Israel (cf. Luke 3.7-9Q; Luke 22.28-30Q), numerous logia are centered on Palestine by their geographical references and the cultural world they assume (cf. only Luke 7.1Q; 10.13-15Q), the bearers of the Q tradition understand themselves to be faithful to the Law (cf. Luke 16.17Q; Luke 11.42Q), and Q polemic is directed against Pharisees (cf. e.g. Luke 11.39b-44Q). 5

As to the dating of Q, Udo Schnelle stated:

The Sayings Source was composed before the destruction of the temple, since the sayings against Jerusalem and the temple in Luke 13.34-35Q do not presuppose any military events. A more precise determination of the time of composition must remain hypothetical, but a few indications point to the period between 40 and 50 CE: (1) Bearers of the sayings tradition, which possibly extends all the way back to pre-Easter times, included both wandering preachers of the Jesus movement as well as local congregations. Thus the conditions in which the Sayings Source originated included both continuity with the beginnings and with the developing congregational structures across the region. (2) The Sayings Source presupposes persecution of the young congregations by Palestinian Jews (cf. Luke 6.22-23 Q; Luke 11.49-51 Q; Luke 12.4-5 Q; 12.11-12 Q). About 50 CE Paul mentions in 1 Thess. 2.14-16 a persecution of Christians in Judea that had already taken place. The execution of James the son of Zebedee by Agrippa I (cf. Acts 12.2) occurred around 44 CE. (3) The positive references to Gentiles in Q (cf. Luke 10.13-15Q; Luke 11.29-31Q; Matt. 8.5-13 Q; Matt. 5.47 Q; Matt. 22.1-10 Q) indicate that the Gentile mission had begun, which is probably to be located in the period between 40 and 50 CE. 6

Most scholars are convinced that of the two Gospels that utilized Q, Luke is more likely than Matthew to have preserved its original sequence. 7 This is chiefly because when Matthew used Mark, he often gathered together in one place stories scattered throughout his Markan source. As a much noted example, Matthew assembled miracle stories dispersed throughout Mark chapters 1,2,4, and 5 into one large collection of miracles in Matthew 8-9. If this tendency for reordering similar kinds of stories was also at work in his treatment of Q, it would make sense that Matthew combines various sayings of Jesus scattered in different portions of Luke. The Beatitudes and the Lord’s Prayer, for example, are in different sections of Luke (chapters 6 and 11) but are joined together as part of the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew (chapters 5-6). It would make less sense to think that Luke randomly disrupted this kind of unity. Luke’s version is therefore probably closer to the original sequence of the stories in Q.

Most scholars are convinced that of the two Gospels that utilized Q, Luke is more likely than Matthew to have preserved its original sequence. 7 This is chiefly because when Matthew used Mark, he often gathered together in one place stories scattered throughout his Markan source. As a much noted example, Matthew assembled miracle stories dispersed throughout Mark chapters 1,2,4, and 5 into one large collection of miracles in Matthew 8-9. If this tendency for reordering similar kinds of stories was also at work in his treatment of Q, it would make sense that Matthew combines various sayings of Jesus scattered in different portions of Luke. The Beatitudes and the Lord’s Prayer, for example, are in different sections of Luke (chapters 6 and 11) but are joined together as part of the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew (chapters 5-6). It would make less sense to think that Luke randomly disrupted this kind of unity. Luke’s version is therefore probably closer to the original sequence of the stories in Q.

The Contents of Q

We cannot know the full contents of Q because it has been lost to us, but it is worth looking into. There are several tables that scholars have put together that demonstrate the content of Q that you can access here. Among the materials that we can say that were in Q are the following:

- The preaching of John the Baptist (Matthew 3:7-10; Luke 3:7-9, 16-17)

- The 3 temptations of Christ in the wilderness (Matthew 4:1-11; Luke 4:1-13)

- The Beatitudes (Matthew 5:3-12; Luke 6:20-23)

- The command to love your enemies (Matthew 5:43-45; Luke 6:27-36)

- The command not to judge others (Matthew 7:1-5; Luke 6:37-42)

- The house on the rock (Matt 7:21-27; Luke 6:46-49)

- The healing of the centurion’s slave (Matthew 8:5-13; Luke 7:1-10)

- The question from John the Baptist while in prison (Matthew 11:1-6; Luke 7:18-35)

- The Lord’s prayer (Matthew 6:9-13; Luke 11:2-4)

- The need for fearless confession (Matthew 10:26-33; Luke 12:2-12)

- The command to not worry about food and clothing (Matthew 6:25-34; Luke 12:22-32)

- Treasure in heaven (Matthew 6:19-21; Luke 12:33-34)

- The parable of the unfaithful slave (Matthew 24:42-51; Luke 12:35-48)

- Entering the kingdom through the narrow door (Matthew 7:13-14, 22-23, Matthew 8:11-12; Luke 13:23-30)

- Jesus’ lament over Jerusalem (Matthew 23:37-39; Luke 13:34-35)

- The parable of the wedding feast (Matthew 22:1-14; Luke 14:15-24)

- The lost sheep and the lost coin (Matthew 18:12-13; Luke 15:4-10)

- On divorce (Matthew 5:32; Luke 16:18)

- Offend a child, it is better a millstone is given (Matthew 18:6-7, Luke 17:1-2)

- On twelve thrones (Matthew 19:29; Luke 22:28-30)

The M and L Sources

There is even less known about the sources known as M and L as we know about Q. Since these are sources that provide material found in either Matthew or Luke alone, there is nothing to compare them with in order to decide their basic character and content. We do not know, for instance, whether M (or L) was only one source or a group of sources, whether it was written or oral. It could represent a single document available to the author of Matthew (or Luke), or several documents, or a number of stories that were transmitted orally, or a combination of all of these possibilities, we just don’t know. What is clear is that these stories came from somewhere, since we have them! To me it would also seem to logically follow that Matthew and Luke are using other manuscripts as source material in their construction of their texts, since this seems to be the basic pattern as we see in the inclusion of the Gospel of Mark in their work. In other words, there were possible multiple M and L sources, similar to what we find when we read Mormon’s account of the textualization of the Book of Mormon. 8

Included in these special sources are some of the most recognizable passages of our New Testament Gospels. For example, the stories from M include the visit of the Magi (Matthew 2:1-12), the flight to Egypt (Matthew 2:13-23), Jesus’ instructions on alms-giving and prayer (Matthew 6:1-8), and his parables of the treasure hidden in the field (Matthew 13:44), the pearl of great price (Matthew 13:45-46), the dragnet (Matthew 13:47-50), the unmerciful servant (Matthew 18:23-35), and the ten virgins (Matthew 25:1-12). Among the stories from L are the birth of John the Baptist and the annunciation to Mary (Luke 1:5-80), the shepherds visiting the infant Jesus, the presentation in the Temple, and Jesus as a twelve year old boy (Luke 2:1-52), the raising of the widow’s son at Nain (Luke 7:11-17), the healing of the ten lepers (Luke 17:11-19), Zacaeus in the sycamore tree (Luke 19:1-10), and the parables of the good Samaritan (Luke 10:29-37)), the prodigal son (Luke 15:11-32), Lazarus and the rich man (Luke 16:19-31), and the unjust judge (Luke 18:1-8).

Why This Matters

Reading the texts of the gospels is critical in our understanding of the development of Christianity. These texts have had profound influence upon Western Civilization. Each of the four gospel writers had significant points of view and oftentimes different views on the nature of Jesus, as well as his birth, death, and resurrection. These differences are significant and should not be downplayed, as if these four authors were simply portraying Jesus in precisely the same way. When modern readers act as if these authors had identical views and work to “harmonize” the gospels, they in a sense create a fifth gospel, one that is neither Matthew nor Mark or Luke. This then can lead to confusion as to why the texts disagree.

As Gaye Strathearn stated:

In teaching both the birth narratives and the Last Supper, teachers should not be afraid of the ambiguity. Rather they should help their students recognize it when it appears and help them understand that in ancient texts, even scriptural texts, there will be times when the appropriate answer to the question “why?” is “here are some possibilities, but at present we don’t have enough information to give a definitive answer.” 9

Seeing the texts for what they are is helpful in our quest for truth. Seeing these texts as both human and divine, each giving a distinct message of hope to the communities that produced and read them in their historical contexts will help us as modern readers to understand the intent of the author and how these texts were used and understood anciently. This in turn will help us as we work to apply these texts in our modern era.

Notes

- John W. Welch, “Textual Consistency,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies [FARMS], 1992), 22–23.

- John Hilton, Textual Similarities in the Words of Abinadi and Alma’s Counsel to Corianton, BYU Studies Quarterly 51, no. 2 (2012).

- Kerry Muhlestein, “Insights Available as We Approach the Original Text,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 15, no. 1 (2006): 61.

- Bart Erhman, The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings, New York, Oxford Press, 2000, p. 78, emphasis added.

- Udo Schnelle, The History and Theology of the New Testament Writings, Fortress Press, 1998, p. 186.

- Op. Cit., p. 186.

- Francis Watson, Gospel Writing: A Canonical Perspective, Eerdmans, 2013, p. 204. See also David Catchpole, The Quest for Q, Bloomsbury T & T Clark, 1993, p. 79.

- John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Sources, lecture September 8, 2011

- Gaye Strathearn, Teaching the Four Gospels: Five Considerations. Religious Educator 13, no. 3 (2012): 79–107.

No Comments

Comments are closed.