The Good Samaritan As A Type

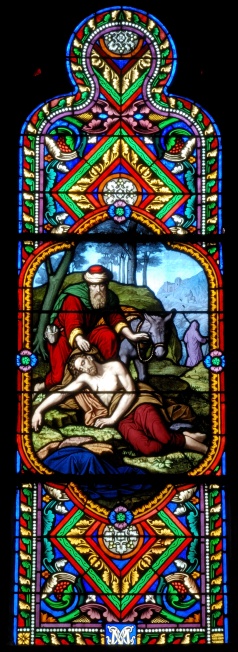

“This parable’s content is clearly practical and dramatic in its obvious meaning, but a time-honored Christian tradition also saw the parable as an impressive allegory of the Fall and Redemption of mankind. This early Christian understanding of the good Samaritan is depicted in a famous eleventh-century cathedral in Chartres, France…

“In the second century A.D., Irenaeus in France and Clement of Alexandria both saw the good Samaritan as symbolizing Christ Himself saving the fallen victim, wounded with sin. A few years later, Clement’s pupil Origen stated that this interpretation came down to him from earlier Christians, who had described the allegory as follows:

‘The man who was going down is Adam. Jerusalem is paradise, and Jericho is the world. The robbers are hostile powers. The priest is the Law, the Levite is the prophets, and the Samaritan is Christ. The wounds are disobedience, the beast is the Lord’s body, the [inn], which accepts all who wish to enter, is the Church. … The manager of the [inn] is the head of the Church, to whom its care has been entrusted. And the fact that the Samaritan promises he will return represents the Savior’s second coming.’

“This allegorical reading was taught not only by ancient followers of Jesus, but it was virtually universal throughout early Christianity, being advocated by Irenaeus, Clement, and Origen, and in the fourth and fifth centuries by Chrysostom in Constantinople, Ambrose in Milan, and Augustine in North Africa. This interpretation is found most completely in two other medieval stained-glass windows, in the French cathedrals at Bourges and Sens…

“In His parables, Jesus taught the essentials of the Father’s plan of salvation. As a type and shadow of this plan, the good Samaritan places our deeds of neighborly kindness here in mortality within the eternal context of where we have come down from, how we have fallen into our present plight, and how the binding ordinances and healing love of the promised Redeemer and the nurture of His Church can rescue us from our present situation, as we serve and live worthy of reward at His Second Coming.

“Seeing the parable in this light invites readers to identify with virtually every character in the story. At one level, people can see themselves as the good Samaritan, acting as physical rescuers and as saviors on Mount Zion, aiding in the all-important cause of rescuing lost souls. Jesus told the Pharisee, ‘Go, and do thou likewise’ (Luke 10:37). By doing as the Samaritan, we join with Him in helping to bring to pass the salvation and eternal life of mankind.

“Disciples will also want to think of themselves as innkeepers who have been commissioned by Jesus Christ to facilitate the long-term spiritual recovery of injured travelers.

“Or again, readers may see themselves as the traveler. As the parable begins, everyone sympathizes and identifies with the lone and weary traveler. We all need to be saved. As the story ends, all travelers can feel safe, having learned that, according to this interpretation, He who ‘was neighbour unto him that fell among the thieves’ (Luke 10:36) is none other than the merciful Christ. He is the most exemplary Neighbor.” 1

A certain man. Early Christians compared this man to Adam. This connection may have been more obvious in ancient languages than in modern translations. In Hebrew, the word adam means ‘man, mankind,’ ‘the plural of men,’ as well as ‘Adam’ as a proper name. Thus, Clement of Alexandria rightly saw the victim in this allegory as representing ‘all of us.’ Indeed, we all have come down as Adams and Eves, subject to the risks and vicissitudes of mortality: ‘For as in Adam all die …’ (1 Corinthians 15:22).

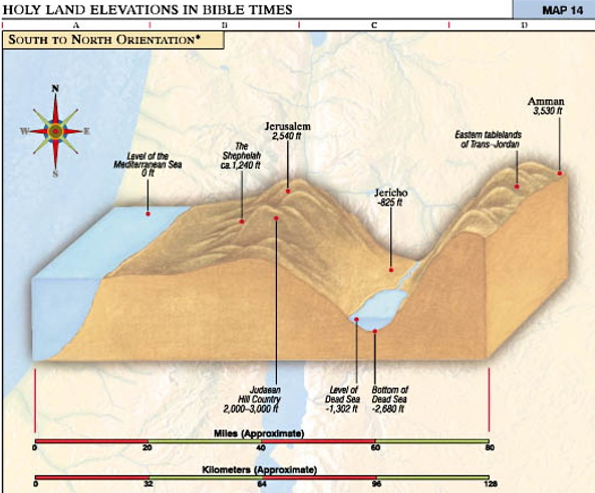

Went down. The early Christian writer Chrysostom saw in this phrase the descent of Adam from the garden into this world—from glory to the mundane, from immortality to mortality. The story in Luke 10 implies that the man went down intentionally, knowing the risks that would be involved in the journey. No one forced him to go down to Jericho. He apparently felt that the journey was worth the well-known risks of such travel on the poorly maintained roads in Jesus’s day.

From Jerusalem. Jesus depicts the person as going down not from any ordinary place but from Jerusalem. Because of the sanctity of the holy temple-city, early Christians readily saw in this element the idea that this person had come down from the presence of God.

To Jericho. Jericho was readily identified with this world. At more than 825 feet (250 m) below sea level, Jericho is the lowest city on earth. Its mild winter climate made it a hedonistic resort area where Herod had built a sumptuous vacation palace. Yet one should note that the traveler in the parable had not yet arrived in Jericho when the robbers attacked. That person was on the steep way down to Jericho, but he had not yet reached bottom.

Fell. It is easy to see here an allusion to the fallen mortal state and to the plight of individual sinfulness: ‘Yea, all are fallen and are lost’ (Alma 34:9).

Among thieves. The early Christian writers variously saw the thieves (or robbers) as the devil and his satanic forces, evil spirits, or false teachers. The Greek word for ‘robbers’ used by Luke implies that these thieves were not casual operators. The traveler was assailed by a band of pernicious highwaymen in a scheming, organized society that acted with deliberate and concerted intent.” 2

James E. Talmage said:

“The road between Jerusalem and Jericho was known to be infested by highway robbers; indeed a section of the thoroughfare was called the Red Path or Bloody Way because of the frequent atrocities committed thereon…Though not definitely stated, the victim of the robbers was almost certainly a Jew; the point of the parable requires it to be so. That the merciful one was a Samaritan, showed that the people called heretic and despised by the Jews could excel in good works. To a Jew, none but Jews were neighbors.” 3

Notes

- John W. Welch, “The Good Samaritan: Forgotten Symbols,” Liahona, Feb. 2007.

- Ibid.

- James E. Talmage, Jesus The Christ, p. 400.