Exodus 18 is an illustration of the problems Moses faced as he led the children of Israel in the wilderness. When his father in law witnesses Moses taking on every problem the Israelites had, he corrects Moses.

The text reads, “And when Moses’ father in law saw all that he did to the people, he said, What is this thing that thou doest to the people? why sittest thou thyself alone, and all the people stand by thee from morning unto even? And Moses said unto his father in law, Because the people come unto me to aenquire of God: When they have a amatter, they come unto me; and I judge between one and another, and I do make them know the statutes of God, and his laws. And Moses’ father in law said unto him, The thing that thou doest is not good. (Exodus 18:14-17 emphasis added)

Jethro then counsels Moses to delegate issues, thus allowing him to have the time necessary to lead the children of Israel in a more effective manner. (see Exodus 18:18-24) I asked the question, “how are teenagers like Moses? How do you find yourself spinning your wheels, not really being effective with your use of time? Have you ever found yourself falling short of what you want to accomplish, knowing that you are close to attaining your goals if you could just find that missing component that would put you over the top and help you achieve your goals?

We examined several examples where individuals and groups used their strengths to accomplish tasks that they ordinarily would not have completed without focused effort – effort that took concentration to not only minimize the exposure of weaknesses but maximized the strengths so as to have the greatest chance of success.

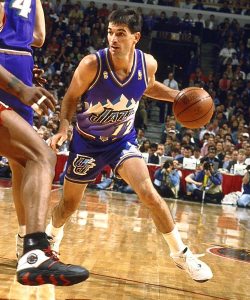

Many of my students know who John Stockton is. He played in the NBA for a number of years and holds the all-time record for assists and steals. What many students did not know is that when the Utah Jazz drafted him 16th in the 1984 draft the fans in the arena booed him. They did not think that a short and relatively unknown player from Gonzaga could help the Utah Jazz. They thought the Jazz were wasting their first round draft pick. The fans did not know what the Utah Jazz’s Frank Layden knew. Frank is known to have been impressed with John’s court vision and basketball IQ. Even though John was very short for an NBA player, he had incredibly large hands. Frank saw what John could do with those hands and understood his potential.

Many of my students know who John Stockton is. He played in the NBA for a number of years and holds the all-time record for assists and steals. What many students did not know is that when the Utah Jazz drafted him 16th in the 1984 draft the fans in the arena booed him. They did not think that a short and relatively unknown player from Gonzaga could help the Utah Jazz. They thought the Jazz were wasting their first round draft pick. The fans did not know what the Utah Jazz’s Frank Layden knew. Frank is known to have been impressed with John’s court vision and basketball IQ. Even though John was very short for an NBA player, he had incredibly large hands. Frank saw what John could do with those hands and understood his potential.

John Stockton used his hands – and his basketball IQ, to lead the Jazz for several division titles and two trips to the NBA finals. He used his strengths to his advantage and found ways to impact the game even though he was often outsized on the court.

Having this conversation in our classes reminded a student of the time he was struggling learning French. He had a father who was a returned missionary from a Spanish speaking country. He changed his foreign language to study Spanish and his father helped him succeed. By utilizing his resources, in this case his father, this young man was able to achieve success learning a foreign language.

In the late 16th century England’s Queen Elizabeth faced a major problem: the king of Spain had designs for an invasion of England. Not having an army or navy anywhere near the size or strength of Spain, she knew that she had to find a way to use England’s strengths against the Spanish military machine without being pummeled.

The following story comes from Robert Greene’s The 33 Strategies of War:

Strengths and weaknesses

When Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) ascended the throne of England in 1558, she inherited a second-rate power: the country had been racked by civil war, and its finances were in a mess. Elizabeth dreamed of creating a long period of peace in which she could slowly rebuild England’s foundations and particularly its economy: a government with money was a government with options. England, a small island with limited resources, could not hope to compete in war with France and Spain, the great powers of Europe. Instead it would gain strength through trade and economic stability.

When Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) ascended the throne of England in 1558, she inherited a second-rate power: the country had been racked by civil war, and its finances were in a mess. Elizabeth dreamed of creating a long period of peace in which she could slowly rebuild England’s foundations and particularly its economy: a government with money was a government with options. England, a small island with limited resources, could not hope to compete in war with France and Spain, the great powers of Europe. Instead it would gain strength through trade and economic stability.

Year by year for twenty years, Elizabeth made progress. Then, in the late 1570s, her situation suddenly seemed dire: an imminent war with Spain threatened to cancel all the gains of the previous two decades. The Spanish king, Philip II, was a devout Catholic who considered it his personal mission to reverse the spread of Protestantism. The Low Countries (now Holland and Belgium) were properties of Spain at the time, but a growing Protestant rebellion was threatening its rule, and Philip went to war with the rebels, determined to crush them. Meanwhile his most cherished dream was to restore Catholicism to England. His short-term strategy was a plot to have Elizabeth assassinated and then to place her half sister, the Catholic Mary Queen of Scots, on the British throne. In case this plan failed, his long-term strategy was to build an immense armada of ships and invade England.

Philip did not keep his intentions well hidden, and Elizabeth’s ministers saw war as inevitable. They advised her to send an army to the Low Countries, forcing Philip to put his resources there instead of into an attack on England- but Elizabeth balked at that idea; she would send small forces there to help the Protestant rebels avert a military disaster, but she would not commit to anything more. Elizabeth dreaded war; maintaining an army was a huge expense, and all sorts of other hidden costs were sure to emerge, threatening the stability she had built up. If war with Spain really was inevitable, Elizabeth wanted to fight on her own terms; she wanted a war that would ruin Spain financially and leave England safe.

Philip did not keep his intentions well hidden, and Elizabeth’s ministers saw war as inevitable. They advised her to send an army to the Low Countries, forcing Philip to put his resources there instead of into an attack on England- but Elizabeth balked at that idea; she would send small forces there to help the Protestant rebels avert a military disaster, but she would not commit to anything more. Elizabeth dreaded war; maintaining an army was a huge expense, and all sorts of other hidden costs were sure to emerge, threatening the stability she had built up. If war with Spain really was inevitable, Elizabeth wanted to fight on her own terms; she wanted a war that would ruin Spain financially and leave England safe.

Defying her ministers, Elizabeth did what she could to keep the peace with Spain, refusing to provoke Philip. That bought her time to put aside funds for building up the British navy. Meanwhile she worked in secret to damage the Spanish economy, which she saw as its only weak spot. Spain’s enormous, expanding empire in the New World made it powerful, but that empire was far away. To maintain it and profit from it, Philip was entirely dependent on shipping, a vast fleet that he paid for with enormous loans from Italian bankers. His credit with these banks depended on the safe passage of his ships bringing gold from the New World. The power of Spain rested on a weak foundation.

And so Queen Elizabeth unleashed her greatest captain, Sir Francis Drake, on the Spanish treasure ships. He was to appear to be operating on his own, a pirate out for his own profit. No one was to know of the connection between him and the queen. With each ship that he captured, the interest rate on Philip’s loans crept upward, until eventually the Italian bankers were raising the rate more because of the threat of Drake than because of any specific loss. Philip had hoped to launch his armada against England by 1582; short of money, he had to delay. Elizabeth had bought herself more time.

And so Queen Elizabeth unleashed her greatest captain, Sir Francis Drake, on the Spanish treasure ships. He was to appear to be operating on his own, a pirate out for his own profit. No one was to know of the connection between him and the queen. With each ship that he captured, the interest rate on Philip’s loans crept upward, until eventually the Italian bankers were raising the rate more because of the threat of Drake than because of any specific loss. Philip had hoped to launch his armada against England by 1582; short of money, he had to delay. Elizabeth had bought herself more time.

Meanwhile, much to the chagrin of Philip’s finance ministers, the king refused to scale back the size of the invading armada. Building it might take longer, but he would just borrow more money. Seeing his fight with England as a religious crusade, he would not be deterred by mere matters of finance.

While working to ruin Philip’s credit, Elizabeth put an important part of her meager resources into building up England’s spy network- in fact, she made it the most sophisticated intelligence agency in Europe. With agents throughout Spain, she was kept informed of Philip’s every move. She knew exactly how large the armada was to be and when it was to be launched. That allowed her to postpone calling up her army and reserves until the very last moment, saving the government money.

Finally, in the summer of 1588, the Spanish Armada was ready. It comprised of 128 ships, including twenty large galleons, and a vast number of sailors and soldiers. Equal in size to England entire navy, it had cost a fortune. The Armada set sail from Lisbon in the second week of July. But Elizabeth’s spies had fully informed her of Spain’s plans, and she was able to send a fleet of smaller, more mobile English ships to harass the Armada on its way up the French coast, sinking its supply ships and generally creating chaos. As the commander of the English fleet, Lord Howard of Effingham, reported, “Their force is wonderful great and strong; and yet we pluck their feathers little by little.”

Finally the Armada came to anchor in the port of Calais, where it was to link up with the Spanish armies stationed in the Low Countries. Determined to prevent it from picking up these reinforcements, the English gathered eight large ships, loaded them with flammable substances, and set them on course for the Spanish fleet, which was anchored in tight formation. As the British ships approached the harbor under full sail, their crews set them on fire and evacuated. The result was havoc, with dozens of Spanish ships in flames. Others scrambled for safe water, often colliding with one another. In their haste to put to sea, all order broke down.

Finally the Armada came to anchor in the port of Calais, where it was to link up with the Spanish armies stationed in the Low Countries. Determined to prevent it from picking up these reinforcements, the English gathered eight large ships, loaded them with flammable substances, and set them on course for the Spanish fleet, which was anchored in tight formation. As the British ships approached the harbor under full sail, their crews set them on fire and evacuated. The result was havoc, with dozens of Spanish ships in flames. Others scrambled for safe water, often colliding with one another. In their haste to put to sea, all order broke down.

The loss of ships and supplies at Calais devastated Spanish discipline and morale, and the invasion was called off. To avoid further attacks on the return to Spain, the remaining ships headed not south but north, planning to sail home around Scotland and Ireland. The English did not even bother with pursuit; they knew that the rough weather in those waters would do the damage for them. By the time the shattered Armada returned to Spain, forty-four of its ships had been lost and most of the rest were too damaged to be seaworthy. Almost two-thirds of its sailors and soldiers had perished at sea. Meanwhile England had lost not a single ship, and barely a hundred men had died in action.

It was a great triumph, but Elizabeth wasted no time on gloating. To save money, she immediately decommissioned the navy. She also refused to listen to advisers who urged her to follow up her victory by attacking the Spanish in the Low Countries. Her goals were limited: to exhaust Philip’s resources and finances, forcing him to abandon his dreams of Catholic dominance and instituting a delicate balance of power in Europe. And this, indeed, was ultimately her greatest triumph, for Spain never recovered financially from the disaster of the Armada and soon gave up its designs on England altogether.

Interpretation

The defeat of the Spanish Armada has to be considered one of the most cost effective in military history: a second-rate power that barely maintained a standing army was able to face down the greatest empire of its time. What made the victory possible was the application of a basic military axiom: attack their weaknesses with your strengths. England’s strengths were its small, mobile navy and its elaborate intelligence network; its weaknesses were its limited resources in men, weaponry, and money. Spain’s strengths were its vast wealth and its huge army and fleet; its weaknesses were the precarious structure of its finances, despite their magnitude, and the lumbering size and slowness of its ships.

Elizabeth refused to fight on Spain’s terms, keeping her army out of the fray. Instead she attacked Spain’s weaknesses with her strengths: plaguing the Spanish galleons with her smaller ships, wreaking havoc on the country’s finances, using special ops to grind its war machine to a halt. She was able to control the situation by keeping England’s costs down while making the war effort more and more expensive for Spain. Eventually a time came when Philip could only fail: if the Armada sank, he would be ruined for years to come, and even if the Armada triumphed, victory would come so dear that he would ruin himself trying to exploit it on English soil.

Understand: no person or group is completely either weak or strong. Every army, no matter how invincible it seems, has a weak point, a place left unprotected or undeveloped. Size itself can be a weakness in the end. Meanwhile even the weakest group has something it can build on, some hidden strength. Your goal in war is not simply to amass a stockpile of weapons, to increase your firepower so you can blast your enemy away. That is wasteful, expensive to build up, and leaves you vulnerable to guerrilla-style attacks. Going at your enemies blow by blow, strength against strength, is equally unstrategic. Instead you must first assess their weak points: internal political problems, low morale, shaky finances, overly centralized control, their leader’s megalomania. While carefully keeping your own weaknesses out of the fray and preserving your strength for the long haul, hit their Achilles’ heel again and again. Having their weaknesses exposed and preyed upon will demoralize them, and, as they tire, new weaknesses will open up. By carefully calibrating strengths and weaknesses, you can bring down your Goliath with a slingshot.