The Enchanted World of the Ancient Near East

One of the things we know as we study the world of the Ancient Near East (ANE) is that the association of religion with belief in the gods and the goddesses of the ANE is far too constricting. People of the ANE believed in an enchanted world. They lived their lives in a hot and sometimes dusty existence, working through their day, stretching themselves to make a life, but they knew that somewhere up in the heavens that there were divine beings and that sometimes these divine beings played a role in the lives of mortals.

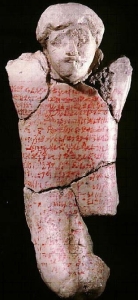

When I use the word “enchanted” I mean that the people of the ANE believed that their world could access the divine realm through the means of incantations, charms, or magic. This magic worldview is seen throughout ANE literature, and it is found in the Bible, since the Bible is a collection of texts from the ANE. People from this place and time lived in a world where all sorts of spiritual entities had power, known and unknown, visible and invisible, animate and inanimate, and these people believed that these spiritual agents had power and in many ways (sometimes in all ways) were responsible for what happens to mortals here in the world below the heavens. Because they believed this, they had formulas by which they could use magic to effect change or to curse others or to cure them.

One of the few religious texts surviving in Akkadian from about 2300 BCE tells of an enchantment ritual used to protect someone who has been tormented with the evil eye. This formula demanded that the person bring a sheep into the victim’s home, hold it up at each corner of the house, and then slaughter the animal:

One black virgin ewe: In (each of) the corners of the house he will lift it up (?). He will drive out the Evil Ey and the [ ]… In the garden he will slaughter it and flay its hids. He proceeds to fill it with pieces of… plant. as he fills it, he should watch. The evil man [ ] his skin. Let [him] car[ry (it) to the river], (and) seven (pieces of…) let him submerge. 1

Certainly nobody would waste a good animal if he didn’t believe that this invocation of magical power would work! The very fact that this ritual was written down is good evidence that the person in this time period believed that this charm had power. In the ANE, fighting off curses uttered by mortals was a real concern, and these curses usually called upon some demon to attack another person, making him sick or even killing them. People of the ANE used curses, especially when the laws of humans failed them 2, or when the social order was broken down. Essentially curses were one way to maintain social order.

The Expression of Curses

The expression of curses in the ANE seems to be very similar to the way that Christians view prayer today in our time and place. Anne Marie Kitz informs us that “curses and blessings are nothing other than prayers uttered by mortals to the divinities. They are neither commands nor demands and there is certainly no assumption on the part of the speaker that either will have instantaneous effect. In the end they are little more than strongly articulated wishes. Deities, on the other hand, articulated curses differently. As supreme beings they did need not invoke a higher power to enact a malediction. Their curses were commands that mortals believed had immediate consequences.” 3

Ancient Israel and Curses

If we now examine ancient Israel, we see these people to be human beings who acted much like the culture in which they lived. King Saul is seen to have attended to a medium for spiritual advice. This medium is shown to have succeeded in summoning the dead prophet Samuel to advise King Saul. In this text we read of the dead still existing, albeit “down there” in the realm of the dead, but still somewhat subject to the rules and laws of the land of the living mortals “up here” above the realm of the dead. Biblical laws forbade consulting mediums and other things that never would have been forbidden if people were not still doing them:

Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live. (Exodus 22:18)

There shall not be found among you any one that maketh his son or his daughter to pass through the fire, or that useth divination, or an observer of times, or an enchanter, or a witch, Or a charmer, or a consulter with familiar spirits, or a wizard, or a necromancer. For all that do these things are an abomination unto the Lord: and because of these abominations the Lord thy God doth drive them out from before thee. (Deuteronomy 18:10-12)

Thou shalt not curse the deaf, nor put a stumblingblock before the blind, but shalt fear thy God: I am the Lord. (Leviticus 19:14)

Why should the cursing of the deaf be forbidden? The implication is that cursing of non-deaf people was permitted, but that cursing the deaf was a bad thing. But why? The answer is that curses were believed to work actual harm; someone who hears that he is being cursed or even hears that this has happened, can work to try and ward off the negative effects of the curse, with prayer or sacrifice to the gods in order to negate these curses. But if someone curses the deaf, well, these people are completely defenseless, as they will never hear of the curse, and therefore the person cursing them is being unfair! A deaf person is the same as a blind person who has a stumbling block placed before them (Leviticus 19:14).

Knowing how the ancients viewed cursings helps us to understand texts like Leviticus 19 and Deuteronomy 18. These texts came out of a culture, and the Lord worked with these people in their culture and in their time and place. Understanding this helps us to understand the content and context of scripture.

Notes

- John H. Elliott, Beware the Evil Eye Volume 1: The Evil Eye in the Bible and the Ancient World – Introduction, Mesopotamia, and Egypt, Cascade Books, 2015, p. 86. See also Benjamim Foster, Before the Muses: Archaic, classical, mature. Bethesda, MD: CDL.Press 1993, p. 55.

- Jan Assman, When Justice Fails: Jurisdiction and Imprecation in Ancient Egypt and the Near East, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 78 (1992), pp. 149-162.

- Anne Marie Kitz, Cursing in the Ancient Near East, The Ancient Near East Today, Vol. 2, no. 12. Accessed 8.23.1018. Anne Marie Kitz is the author of the book Cursed Are You!: The Phenomenology of Cursing in Cuneiform and Hebrew Texts.

No Comments

Comments are closed.