Historical Background – D&C 91

“On 8 March 1833, Joseph Smith received a revelation (D&C 90) concerning the First Presidency of the Church and its role in taking the gospel to the world. In that revelation, it was also indicated to Joseph that he was to continue his work on the Joseph Smith Translation by completing his inspired revision of “the prophets” (D&C 90:13), that is, the Old Testament books. Accordingly, on the very next day, 9 March 1833, Joseph resumed work on the Joseph smith Translation in his quarters above Newel Whitney’s store. It appears, however, that a question soon arose concerning the exact definition of “the prophets.” The Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches include in their Old Testament a dozen or so books known as ‘the Apocrypha,’ which they consider to be inspired scripture and the word of God. Unfortunately, ancient Hebrew manuscripts of the Bible do not include these books, so Protestants, following the example of Martin Luther, have generally excluded the Apocrypha from their bibles. However, the copy of the King James Bible that Joseph Smith used in his work on the Joseph Smith Translation did contain the Apocrypha at the end of the Old Testament, so naturally the question arose: Exactly which books belong in the Old Testament? Were the Apocrypha part of “the prophets” and therefore part of Joseph’s translation obligation according to the instructions in Doctrine and Covenants 90:13, or were they later additions to the Bible and therefore beyond the scope of his translation of the biblical scriptures?”[1]Stephen E. Robinson, H. Dean Garrett, A Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants, [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 2001] 3:165-166.

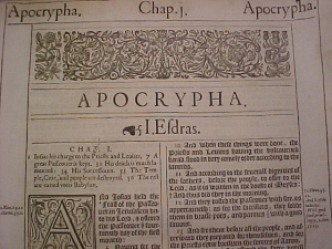

What is the Apocrypha?

The Apocrypha is a group of books historically part of the Old Testament. Only fourteen apocryphal books included in the Septuagint (which was used by the New Testament church) were later included in the Christian Bible. Jerome included some of these in the Latin Vulgate but referred to them as the Apocrypha, as they were not in the Hebrew Bible. Luther separated the books and attached them to the end of his translation of the Old Testament. They were included in nearly all English versions until 1827, when the British and American Protestant Bible societies decided to omit them. The Catholics, however, kept these books as canon.[2]Gerald E. Jones, “Apocryphal Literature and the Latter-Day Saints,” in Apocryphal Writings and the Latter-day Saints, ed. C. Wilfred Griggs (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young … Continue reading

One biblical scholar wrote: “Great values reside in the Apocrypha: the Prayer of Manasseh is a notable piece of liturgy; I Maccabees is of great historical value for its story of Judaism in the second century before Christ, the heroic days of Judas Maccabeus and his brothers, when Pharisaism had its rise. The additions to Esther impart a religious color to that romantic story; Judith, Susanna, and Tobit while fascinating pieces of fiction, were meant by their writers to teach important lessons to their contemporaries. Wisdom and Ecclesiasticus are among the masterpieces of the Jewish sages.

“But to us this appendix of the Old Testament is important as forming a very necessary link between the Old Testament and the New; and if we had no Old Testament at all, the Apocrypha would still be indispensable to the student of the New Testament, of which it forms the prelude and background…

“The period of which the books in this volume are a significant monument, roughly the last two centuries B.C., is of central importance for the cultural history… It is very likely, for example, that the organization and discipline of the Essene-like community of Qumran near the Dead Sea were influenced by Pythagorean patterns; and the path from the Essenes to Christianity is straight and smooth.”[3]Edgar J. Goodspeed, translator, The Apocrypha, [Random House: New York, 1959], v-xiii.

The books of the Apocrypha were scattered throughout the Old Testament. Their titles with a brief description are provided:

- First Book of Esdras– An account of the religious reforms of King Josiah (640-609 B.C.) is contained in the First Book of Esdras along with the subsequent history down to the destruction of the temple in 587 B.C. It then describes the return of exiles under Zerubbabel and events that followed, of which we have another account in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. Incidentally, Esdras is another form of the name Ezra. In Esdras 3:1-5:6 is a story that tells how Zerubbabel, by his wisdom as page of Darius, won the king’s favor and obtained permission to restore the captive Jews to their own country. At the center of this text is a tale known as “The Dispute of the Courtiers”, a narrative where three pages of King Darius make arguments as to what is “shall be the strongest.” The first writes, “wine”, the second, “the king”, the third “Women, but above all things, truth beareth away the victory” (1 Esdras 3:12).[4]All of the references to the Apocryphal texts can be accessed at the Internet Sacred Text Archive. See also: The Apocrypha

- They then explain how they arrived at these conclusions. The victor of the contest, the third page, asks as a reward the return of the Jews to their homeland. His name is given as “Zerubbabel” (Esdras 4:13). Of the date of the compilation of the book we know nothing save that its contents were known to Josephus (c. 100 C.E.).

- Second Book of Esdras– (also identified as Fourth Ezra). This work contains seven visions or revelations given to Ezra, who is represented as grieving over the afflictions of his people and confused at the triumph of gentile sinners. The book is marked by a tone of deep sadness. The only note of consolation is the thought of the retribution that is to fall upon the heads of the gentiles who have tormented Jews. The references to the Messiah deserve special notice (7:28-29; 12:32; 13:32, 37, 52). Many scholars conclude that the book was composed in the first century A.D.

- Book of Tobit-A tale of Tobit’s righteousness and his son’s quest for a wife. Story demonstrates Hellenistic influence of author. The story told in the book of Tobit is as follows. Tobit is a Jew of the tribe of Naphtali, living in Nineveh, and is a pious, God-fearing man who is very strict in his observance of the Jewish law. Trouble comes upon him, and he loses his eyesight. Later, he sends his son Tobias to fetch ten talents of silver, which he had left in the hands of his kinsman Gabael who dwells at Rages in Media. Tobias takes a traveling companion with him, who is in reality the angel Raphael. On the way, they stop at Ecbatana and lodge at the house of one Raguel, whose daughter Sara has through the evil spirit Asmodeus been seven times deprived of husbands on the night of wedlock. Tobias on the ground of kinship claims her in marriage, and her parents consent. By supernatural means, Tobias is able to expel the demon Asmodeus. During the marriage festivities, the angel Raphael journeys to Rages and obtains the money from Gabael. Tobias and his wife then return to Nineveh; and by further application to supernatural means, Tobias is able to restore his father’s sight. Raphael, having revealed his true nature, disappears. Tobit breaks forth into a song of thanksgiving. He and his family end their days in prosperity. The story’s general character seems to show that it was a writing in praise of a life spent in devout consistency with the Jewish law, even in a strange land.

- Book of Judith– The book of Judith describes a romantic event in the history of the Jews that is, the destruction of the Assyrian general Holofernes by Judith, a rich and beautiful widow of Betulia.

- Additions to the Book of Esther– The other chapters of Esther expand in greater detail the narrative of the canonical book of Esther. Their object is to illustrate God’s gracious hearing of prayers and His deliverance of His people, the Jews, from the grasp of gentiles.

- Wisdom of Solomon– This book reads like Proverbs, with many references to the importance of wisdom, which is fitting considering the name of this book.

- Ecclesiasticus or the Wisdom of Sirach– In style and character, the book resembles the canonical book of Proverbs. The greater part is occupied with questions of practical morality. Among its subjects are friendship, old age, women, avarice, health, wisdom, anger, and servants. The name Ecclesiasticus dates from the time of Cyprian, bishop of Carthage (A.D. 248-58). It has no connection with the Old Testament book of Ecclesiastes.

- Book of Baruch– Baruch discusses the Fall of Jerusalem to Babylon as a consequence of the Jews violation of the Mosaic Law and covenant. Purportedly contains a letter written by Jeremiah warning the Jewish captives to avoid the idols of Babylon during their captivity. This book takes readers to the fifth year after the destruction of Jerusalem by the Chaldeans. It is likely that this book was composed at a later date.

- Story of Susanna– This is a story that describes how Daniel as a young man obtained the vindication of Susanna from a shameful charge of adultery and won the condemnation of the two wicked men who had sought her destruction. Constantinople sees Susanna as “a glorious example to women of all times. Susanna endured a severe fight, more severe than that of Joseph. He, a man, contended with one woman; but Susanna, a woman, had to contend with two men.[5]Bruce M. Metzger, An Introduction to the Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1957), 112. See also Steven C. Walker, “‘Whoso Is Enlightened . . . Shall Obtain Benefit’: The Literary … Continue reading

- Song of the Three Children-This work claims to be the prayers, conversation, and praise of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abed-nego (they are called Ananias, Azarias, and Misael in v. 66) when they were in the midst of the burning, fiery furnace.

- Story of Bel and the Dragon– This contains a story of Daniel demonstrating to the Babylonian king that his god, Baal (Bel), has no strength or life. In this narrative, we find two more anecdotes related to Daniel. In the first, Daniel discovers for King Cyrus the frauds practiced by the priests of Bel in connection with the pretended banquets of that idol. In the second, we read the story of Daniel’s destruction of the sacred dragon that was worshiped at Babylon. Both stories serve the purpose of bringing idolatry into ridicule.

- Prayer of Manasseh– This is a short work of 15 verses which claims to be the prayer which Manasseh gave in 2 Chronicles 33:18-19 whereby he asked God to forgive him for his idolatry while he was captive in Babylon. It was probably written in the first or second century BCE.

- First Book of Maccabees-This is an account of the Maccabean uprising of 167-134 BCE. It recounts with sharp detail the whole of the Maccabean movement from the accession of the Seleucid king Antiochus Epiphanes (175) to the death of Simon the Hasmonean (135). The chief divisions of this document from this stirring period are the persecution of Antiochus Epiphanes and the national rising led by the aged priest Mattathias, the heroic war of independence under the lead of Judas the Maccabee, and the recovery of religious freedom and Jewish political independence under Jonathan (160-143) and Simon (143-135).

- Second Book of Maccabees– The Second Book of Maccabees deals with the history of the Jews during a 15 year span (175-160 BCE) and covers part of the period described in First Maccabees. This work affirms the doctrine of the Resurrection from the dead and encouraged the Jews to adopt Hanukkah, a non-biblical festival that commemorates the rededication of the temple in 164 BCE.

DC 91:1 There are many things contained therein that are true

The Apocrypha tells of Ezra’s interesting millennial vision wherein he sees the righteous “clothed in white” having received “splendid garments from the Lord.” He describes the King of kings as follows:

I Ezra, saw on Mount Zion a great throng which I could not count, and they all praised the Lord with songs.

And in the midst of them was a youth of lofty stature, taller than all the rest, and he put crowns upon the heads of each of them, and he was still more exalted. But I was possessed with wonder.

Then I asked the angel, and said, “Who are these, sir?”

And he answered and said to me, “These are those who have laid aside their mortal clothing, and have put on immortal, and have confessed the name of God; now they are crowned and receive palms.”

And I said to the angel, “Who is that young man, who puts the crowns on them and the palms in their hands?”

He answered and said to me, “He is the Son of God, whom they confessed in the world.” (II Esdras 2:39-47)

DC 91:2 There are many things contained therein that are not true

Taken as a whole, in my opinion, very little of the Apocrypha contains teaching that would lead one astray per se. However, much of the text is either not that instructive or uninspired at first glance. The phrase “interpolations by the hands of men” is a perfect description. Some of the texts, while appearing uninspired at first notice, become richer as one is exposed to some of the nuances of ancient literature and how the ancients perceived the temple. Judith is an example of this. Some of the more questionable passages are given below.

The book of Tobit is remarkable for its lack of humility. It is an autobiographical text encouraging us to honor and revere Tobit. Tobit boasts of his great acts of charity:

I, Tobit, walked all the days of my life in ways of truth and uprightness. I did many acts of charity for my brothers and my nation… A tenth part of all my produce I would give to the sons of Levi, who officiated at Jerusalem… all my brothers and relatives ate the food of the heathen, but I kept myself from eating it, because I remembered God with all my heart… In the times of Shalmaneser I used to do many acts of charity for my brothers. I would give my bread to the hungry and my clothes to the naked, and if I saw one of my people dead and thrown outside the wall of Nineveh, I would bury him. (Tobit 1:3-17)

The Second Book of Esdras emphasizes that Adam is responsible for the consequences of the Fall. In doing so, the writer demonstrates his poor understanding of the Plan of Salvation, what D&C 91 certainly would label as “interpolations by the hands of men”:

For the first Adam, burdened with a wicked heart, transgressed and was overcome, as were also all who were descended from him. So weakness became permanent, and the Law was in the heart of the people with the evil root; and what was good departed, and what was evil remained. (2 Esdras 3:21-22)

It would have been better for the earth not to have produced Adam, or when it had produced him compelled him not to sin. For what good is it to all men to live in sorrow and expect punishment after death? O Adam, what have you done? For although it was you who sinned, the fall was not yours alone, but also ours for we are descended from you. (2 Esdras 7:46-48)

The apocalyptic tone of II Esdras is impressive and appealing. Not all of the content, however, is trustworthy. It tries to describe some very questionable signs of the Second Coming as follows:

…infants a year old shall talk, and women with child will bring forth untimely infants at three or four months, and they will live and dance…

…[in that day] wild animals will go outside their [dens], and women in their uncleanness will bear monsters. (2 Esdras 6:21; 5:8)

DC 91:4-5 whoso readeth it… [who] is enlightened by the Spirit shall obtain benefit therefrom

Robert J. Matthews spoke in favor of a tolerant approach toward [apocryphal writings]. Labeling something apocryphal or canonical is the work of people or councils, he said, and is sometimes influenced by preference and religious conditions. ‘Items that are regarded as canon by one group might not be by another. The selection of what is apocryphal and what is canonic varies with who is making the decision.

“‘There is much interesting and useful reading in the apocryphal literature,’ he continued. ‘And one can often decide what is correct by the Spirit. But if we try to make those decisions without the Spirit, we may make colossal errors. Much apocryphal literature is obviously spurious,’ he warned. However, ‘the presence of ideas and names in latter-day revelation that are not found in the Bible but are found in apocryphal writings should quicken our interest in these ancient things.’”[6]Robert J. Mathews, “News of the Church,” Ensign, Dec. 1983, 70.

Another LDS teacher has written: “Accordingly, it has been the position of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that the Apocrypha are not scripture, but that they may be of value if read with the Spirit. One who studies the gospel aided by the Spirit is equipped to discern truth from error in the Apocrypha. The words to one of our hymns, ‘Now Thank We All Our God’ (Hymns, no. 120), were taken from the Apocryphal book of Ecclesiasticus (50:22-24). First and Second Maccabees provide valuable historical information for the period between the Old and New Testament. The Apostle Paul seems to have quoted more than once (Eph. 6:13-17; Rom. 1:20-31, Rom. 9:20-22) from the Wisdom of Solomon, a book which teaches, among other things, the premortal existence of souls (8:19f) and the creation of the universe out of unformed, uncreated matter (11:17). The Prayer of Manasseh is surely one of the most beautiful prayers of repentance ever written.

“Yet these same books also contain passages that are incompatible with the principles of the gospel-hence the important limitations imposed by the Lord in his discussion of the Apocrypha in Doctrine and Covenants 91. Furthermore, the revelation considers only the Old Testament Apocrypha. Since that revelation was given, other apocryphal literature has been discovered. Obviously, section 91 does not address such recent discoveries as the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Nag Hammadi codices, and other newly found manuscripts, but the principle of that revelation undoubtedly still applies: ‘Therefore, whoso readeth it, let him understand, for the Spirit manifesteth truth.’ (D&C 91:4.)[7]Stephen E. Robinson, “Background for the Testaments,” Ensign, Dec. 1982, 26.

DC 91:6 whoso receiveth not by the Spirit, cannot be benefited

“When compared with the scriptures, the Apocrypha is less fruitful soil for spiritual growth without greater than usual assistance from the Spirit… While historians and scholars can find much in these documents of importance to their research, average Church members will receive a greater spiritual return on their investment of time by reading the Bible and the other standard works than they will by reading the Apocrypha.”[8]Stephen E. Robinson, H. Dean Garrett, A Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants, [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 2001] 3:169.

References

| ↑1 | Stephen E. Robinson, H. Dean Garrett, A Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants, [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 2001] 3:165-166. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Gerald E. Jones, “Apocryphal Literature and the Latter-Day Saints,” in Apocryphal Writings and the Latter-day Saints, ed. C. Wilfred Griggs (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1986), 53–107. |

| ↑3 | Edgar J. Goodspeed, translator, The Apocrypha, [Random House: New York, 1959], v-xiii. |

| ↑4 | All of the references to the Apocryphal texts can be accessed at the Internet Sacred Text Archive. See also: The Apocrypha |

| ↑5 | Bruce M. Metzger, An Introduction to the Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1957), 112. See also Steven C. Walker, “‘Whoso Is Enlightened . . . Shall Obtain Benefit’: The Literary Art of the Apocrypha,” in Apocryphal Writings and the Latter-day Saints, ed. C. Wilfred Griggs (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1986), 109–24. |

| ↑6 | Robert J. Mathews, “News of the Church,” Ensign, Dec. 1983, 70. |

| ↑7 | Stephen E. Robinson, “Background for the Testaments,” Ensign, Dec. 1982, 26. |

| ↑8 | Stephen E. Robinson, H. Dean Garrett, A Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants, [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 2001] 3:169. |

No Comments

Comments are closed.