Was the birth of Moses as found in Exodus based on the Sargon birth story?

In movies today heroes destined for greatness usually start with humble origins. Think about Spider-Man, Star-Wars, and The Hobbit. In these films, the heroes are generally modest people, who, when confronted with extraordinary circumstances, either find out that they have great abilities, or exhibit greatness in the midst of incredible opposition and evil. They are either orphans (Spider-Man, Star Wars, Harry Potter, Batman, Superman, Annie), abandoned (Star Wars 7), or ordinary everyday guys turned hero (The Hobbit, Lord of the Rings). This literary theme goes back to ancient times, when stories were first transformed from oral tradition to written form. Writers of these stories use the abandoned child theme to identify a character that rises from anonymity to the rank of hero. It’s a theme or pattern found in the biblical account of Moses’ birth. But is that really the whole story?

Moses’ story begins when Pharaoh feels threatened by the growing Hebrew population in Egypt and commands that all Hebrew male infants be killed (Exodus 1). Moses’ mother Jochebed יוֹכֶבֶד hides her newborn son for three months and then devises a dangerous but calculated plan: She sets Moses floating down the Nile “by the river’s brink” (Exodus 2:3) in a basket made of bulrushes, waterproofed with “slime and pitch” (Exodus 2:3). Moses’ older sister, Miriam, watches as the basket floats to where the daughter of Pharaoh bathes. The Lord uses these circumstances to bring Moses under the protection of Egypt’s ruler (Exodus 2:4–10).

Ancient literature outside the Bible attests to several stories in which a child, perceived as a threat by an enemy, is abandoned and later spared by divine intervention. There are perhaps as many as 72 stories like this that survive from the literature of ancient world, according to some scholars.1

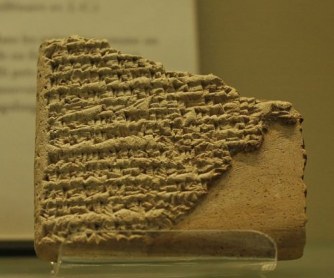

The Mesopotamian work known as the Sargon Birth Legend offers the most striking parallels to the Exodus account of Moses’ birth. It relates the birth story of Sargon the Great, an Akkadian emperor who ruled a number of Sumerian city-states around 2300 BCE, around 800 years before Moses. The infant boy is born into great peril: His mother is a high priestess, and he is illegitimate. As a result of these circumstances, his mother decides to place him on a river in a reed basket. The boy is rescued and raised by a gardener named Akki. He lives as a modest gardener in Akki’s service until the goddess Ishtar takes an interest in him, and puts him on a path to kingship.

To be direct, the story of the birth of Moses is not unique in the ancient Near Eastern world. Rather, it is stories such as this that bring us face to face with what is in fact characteristic of the Old Testament as a whole. It is stories like this that teach us what we are reading when we pick up the Old Testament. Wouldn’t we expect a biblical narrative to take on a literary quality that fits with its historical setting? I believe that the very nature of a revealed, inspired text is that it takes on the “feel” of its place and time in history. In other words, God, when he speaks in scripture, speaks to “real” people, in a real place and time. Revelation does not just come to us in a vacuum! It comes in a cultural place and time. And, when God speaks to man, he speaks to him according to his (man’s) language (see D&C 1:24). God has to meet us somewhere, and it is in our time and place that he does so. He meets us where we are, and works to bring us to where he is. To me, this really helps me understand the scriptures – a story of man in his time and place, where he is introduced to God. God then communicates to man in this setting.

Is the Sargon birth narrative the source for the Moses account in the Bible?

Some have assumed that the biblical story of Moses’ birth was based on the Sargon Birth Legend, and this is possible. Could the ancient writer of this text have used this account to tell Moses’ story? Perhaps, and this does not diminish the truth of scripture. Rather, the word becomes “incarnate”; it enters into the very lives of God’s people. On the other hand, even though the ancient Sumerian accounts of Sargon the Great date back to his lifetime, the legendary account of his birth is known from only four fragmentary tablets—three from the Neo-Assyrian period (934–605 BCE) and one from the Neo-Babylonian period (626–539 BCE). 2 During the Neo-Assyrian period an Assyrian king took the name Sargon II and likely decreed the legends to be written about his namesake (722–705 BCE). By doing so, he would have associated himself with this ancient legend. This would suggest that the Sargon birth legend was composed for propaganda reasons well after the life of Moses. In stating this, I am aware that these same kind of accusations can be used against the writers of the Pentateuch as well. 3

Turning a literary approach upside down

The existence of stories like the Sargon Birth Legend help us understand the biblical story. They show that the abandoned child theme was a popular literary approach for the writers of this ancient text. They used it to introduce a figure who rises from commonplace beginnings after gaining favor from the divine. I believe that we will never be able to completely settle the complex issue of the relationship between “history” and “literature” here and I don’t think it is that important. To me, the idea that this story contains elements from the realm in which it is written proves that God works with man in his world, and he meets man where he is, in his time and place. Certainly this birth story had attention grabbing quality!

Moses’ story is about more than parallels with Sargon, however. While Moses does find favor and protection in the house of Pharaoh, his life takes a surprising turn when the events of Exodus 2:11-15 develop. He ends up leaving Egypt to become a humble shepherd in the land of Midian (Exodus 2:15-25). From this point on, the “abandoned infant” story is recontextualized: In the wilderness, in the mountain of Horeb (Exodus 3:1), Jehovah appears to the man Moses, who will become the mighty prophet. Moses then changes the course of history forever, and a nation of slaves becomes of the nation of Israel, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Moses stands out against the stories of the ancient cultures because he isn’t promoted like their chosen figures, rather he is saved by God and then spends many of his days in relative obscurity as a common man. This common man then meets God, who uses Moses to redeem His people. While there are elements in this story from ancient sources, this story is unique in that it emphasizes the sovereignty of God and his power to redeem man – in other words, this story isn’t about Moses at all, really. The prophet Nephi understood this, and he used the story of Moses to find motivation to follow the commands of God and have God use him to do great things.4 The story of Moses is really about God and his work in your life, and his relationship to you. God is able to do his work, and, if we allow him, he can use us as he used Moses to accomplish great things.

Notes

- Donald Redford and Brian Lewis have provided a detailed analysis of many “infant exposure” stories from the ancient world, concluding that there are 72 of these types of stories extant from the ancient world. D.B. Redford, “The literary motif of the exposed child”, Numen (14) 1967: 209-228. See also Brian Lewis, The Sargon Legend: A Study of the Akkadian Text and the Tale of the Hero that was Exposed at Birth (Cambridge, Mass.: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1980).

- Westenholz, Joan Goodnick (January 1984). “Review of The Sargon Legend: A Study of the Akkadian Text and the Tale of the Hero Who Was Exposed at Birth. By Brian Lewis”. Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 43 (1).

- David Sperling, The Original Torah: The Political Intent of the Bible’s Writers. Reappraisals in Jewish Social and Intellectual History. New York, New York University Press, 1998. It is important to note, that from the world of the ANE, that the prophet Nephi fits this description perfectly. He is writing history, from his point of view, to give a narrative to future people that explains his reasons for things such as who should be king, who should maintain the sacred scriptural history, who has claim to land, etc. In other words, scholars of our time would say that Nephi was writing “propaganda” – certainly he was! This was one of the purposes of scripture in the ancient world, to legitimize kingship, beliefs, claims to land and authority, and so forth.

- Nephi and the Exodus, Ensign, April, 1987. See also: George Tate, “The Typology of the Exodus Pattern in the Book of Mormon,” in Literature of Belief (Provo: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1981), pp. 245–62.

No Comments

Comments are closed.